By Brian Boone

Maybe you had a video game or a system on your holiday list — to get for others or hopefully received. Will the games so excitedly unwrapped be all time classics… or will they join the ranks of these duds?

HyperScan

All the major video game systems are manufactured by electronics companies. In 2006, toymaker Mattel joined the fray with the HyperScan. It stayed competitive by offering the system for $70 and games for $20, about a third of the prices of the other guys’ wares. That’s because Mattel tried to operate on a micro-transactions model. If players wanted to advance beyond the first few levels of a game, or try new characters, or access necessary tools and gear, they had to download them by purchasing scannable $10 packs of IntelliCards, which offered different assets at random. Only five games were released (each with dozens of IntelliCards), mostly featuring Marvel superheroes, and the system sold so poorly that within six months, Mattel ended production and discounted the stock of the system, games, and cards to $10, $2, and $1, respectively.

Virtual Boy

Virtual reality was heralded as the next big thing in 1995, and one of the first products on the market to promise an immersive, computerized experience was Nintendo’s Virtual Boy. To keep costs low while also maximizing what technology allowed at the time, the $180 system looked like binoculars on a mini-tripod. Users held their face up to the console to look inside, where they were met with blurry images in a weird world where everywhere was rendered in shades of black and red that simulated a 3-D effect. Nintendo fielded complaints of both neck cramps and eye strain, and only 700,000 bought a Virtual Boy, making it the company’s least-popular system ever. Only 14 games were ever made, including thrilling-sounding titles like Virtual Fishing.

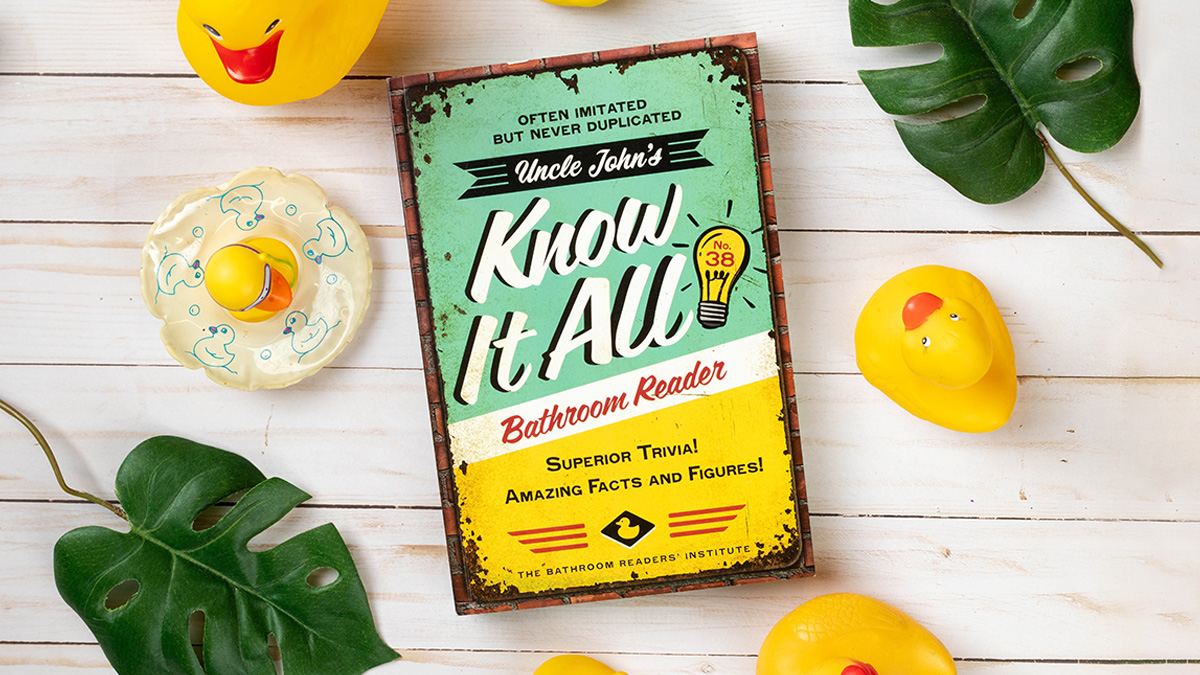

Get Uncle John's Know It All Bathroom Reader Today!

VecTrex

Milton Bradley, a publisher of board games, broke into the electronic gaming industry in 1982 with the VecTrex. At the time, Atari has the hot name in video games, and the VecTrex was marketed as everything Atari wasn’t, and also better. The Atari 2600 plugged into a TV and had crude, pixelated graphics. The VecTrex’s display was vector-based, an atmospheric and depth-creating system of lines. Also, VecTrex’s didn’t require a TV set because it had a built-in monitor. Milton Bradley couldn’t break Atari’s virtual monopoly or popularity, and the VecTrex didn’t sell well, even when its price was slashed from $200 to $79.

Commodore 64 Game System

In the early to mid-1980s, a lot of households skipped the video game system in favor of the Commodore 64, a full-service home computer that could also play hundreds of games with graphics superior to those compatible with an Atari console. Following the arrival of various Nintendo and Sega systems, and affordable and better computers, the Commodore 64 was virtually obsolete and forgotten by 1990, at which point the Commodore 64 Game System, or C64GS, hit stores. Intended to plug into a TV like a Super Nintendo or Sega Genesis, the C64GS came with an old-fashioned and antiquated joystick; the other system had long since moved onto keypad-style controllers. Commodore didn’t do anything to operate its hardware or software. Intending to compete with the sophisticated graphics on other systems, the C64GS offered old games that could be played on a TV. Some of them didn’t even work — the keyboard was used in many of its ‘80s games, and that wasn’t a feature on the C64GS. Only 2,000 units sold (out of 20,000 produced), making this likely the most unpopular video game system of all time.