THE TUPPERWARE STORY

Today the word Tupperware is a generic term for any plastic food container

with a sealable lid. That’s thanks to two people: Earl Tupper, inventor

of the product that bears his name, and Brownie Wise, who has

been all but erased from the company’s history.BLACK GOLD

In the fall of 1945, a plastics manufacturer named Earl Tupper tried to place an order for plastic resin, one of the key ingredients in plastic, with the Bakelite Corporation. But the material was in short supply, and Bakelite couldn’t fill his order. When Tupper asked if they had anything else for him to work with, the company gave him a black, oily lump of polyethylene slag, a rubbery by-product of the petroleum refining process that collected at the bottom of oil barrels. Bakelite, makers of an early plastic by the same name, couldn’t find a use for the waste product, and neither could the chemical giant DuPont. Both companies had plenty of the stuff lying around. They told Tupper he could have as much as he wanted.Tupper spent months experimenting with different blends of polyethylene—“Poly-T,” as he called it—and molding them at different pressures and temperatures. He eventually came up with a process for forming it into brightly colored cups, bowls, and other household items. A year later he patented the idea that he’s most famous for: the “Tupperware seal,” which provided a spill-proof, airtight seal between Tupperware containers and their lids. (He borrowed the idea from paint-can lids.) Tupper called his first sealable container the “Wonderbowl.”

UNDER COVER

Today plastic containers with airtight lids are so common that it’s easy to forget just how revolutionary Tupperware was when it was introduced in the late 1940s. In those days, if you wanted to preserve food in the refrigerator, you could cover a dish with wax paper or foil. (Plastic wrap was still a few years away.) If you wanted something that you didn’t have to throw away after a few uses, you could cover the dish with a shower cap or a damp cloth. Glass containers were available, but they weren’t cheap. They weren’t airtight, either, and if you dropped them, they shattered into tiny, razor-sharp pieces—not a good thing during the post-war Baby Boom, when lots of households had small children underfoot. None of these options were very satisfactory. It was difficult to keep food fresh for more than a day or two, or to keep everything in the fridge from smelling like everything else in the fridge.BLACK SHEEP

And yet for all the advantages that Tupperware had to offer, it just sat on store shelves, even when Tupper promoted the launch with national advertising. Consumers just weren’t interested. Part of the problem with Tupperware was that a lot of consumers couldn’t figure out how to work the lids. Some people even returned their Tupperware, complaining that the lids didn’t fit. But the real problem with Tupperware was that it was made of plastic. In those very early days of the plastics revolution, the stuff had a bad reputation: Many early plastics were oily; some were flammable. (They were smelly, too. One of the main ingredients in Bakelite was formaldehyde—the main ingredient in embalming fluid.) Some plastics were brittle and prone to chipping and cracking; others peeled, disintegrated, or “melted” and became deformed in hot water.Tupperware didn’t have any of these problems—it was odorless, non-toxic, lightweight. It was sturdy yet flexible and kept its shape in hot water. And if you dropped it, it bounced without spilling its contents. But consumers didn’t know all that, and they were so turned off by earlier plastics that they didn’t bother to find out.

SILVER LINING

As Earl Tupper pored over the dismal sales figures, he noticed that Tupperware was popular with two types of customers: 1) mental hospitals, which preferred Tupperware cups and dishes to aluminum because they didn’t dent or make noise when patients threw them on the floor; and 2) independent salespeople who sold goods distributed by Stanley Home Products, one of the companies that pioneered the “party plan” sales method.Stanley salespeople hawked their wares by recruiting a house- wife to host a party for her friends and acquaintances. At the party, the salesperson demonstrated Stanley products—mops, brushes, cleaning products, etc.—in the hopes of selling some to the guests. Quite a few companies still sell goods using the home party system, and if you’ve ever been invited to such a party, you probably know that they aren’t always the most pleasant of experiences. A lot of people attend only out of guilt or a sense of obligation to the host and buy just enough merchandise to avoid embarrassment. The same was true in the late 1940s: People could buy cleaning products anywhere, which made it kind of irritating to have to sit through a Stanley demonstration just because a friend had invited them. Even the Stanley salespeople knew it, and that was why growing numbers of them were adding Tupperware to their Stanley offerings.

LIFE OF THE PARTY

Tupperware was no mop or bottle of dish soap. It was something new, a big improvement over the products that had come before it. Once the salesperson explained its advantages and demonstrated how the lids worked—they had to be “burped” to expel excess air and form a proper seal—people were eager to buy it. They bought a lot of it, too: Tupperware sold so well at home parties that many Stanley salespeople were abandoning the company entirely and selling nothing but Tupperware.One of the most successful of the ex-Stanley salespeople was a woman named Brownie Wise. By the early 1950s, she was ordering more than $150,000 worth of Tupperware a year for the sizable home party sales force she’d built up, this at a time when Earl Tupper couldn’t sell Tupperware in department stores no matter how hard he tried. In April 1951, he hired Wise and made her a vice president of a brand-new division called Tupperware Home Parties, headquartered in Kissimmee, Florida. (Tupper remained in Leominster, Massachusetts, overseeing the company’s manufacturing and product design.) Brownie’s new job was to build the company’s sales force, just as she’d been so successful building her own.

Tupper also pulled Tupperware from department stores. From then on, if you wanted to buy Tupperware (or any plastic container with an airtight lid, since Tupper controlled the patent), you had to buy it from a “Tupperware lady.” …

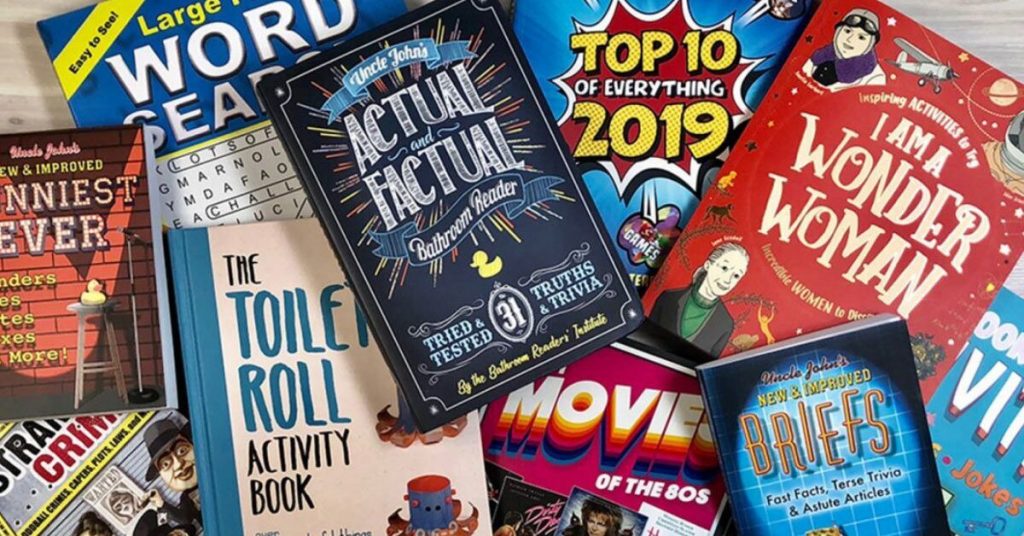

That’s another excerpt from the brand new Uncle John’s 24-KARAT GOLD Bathroom Reader. You can get the rest of that story (there’s much more, including how Tupper and Wise fell out), and hundreds of other stories – at 30% off the usual price as part of our annual HOLIDAY SALE! And that’s 30% of ALL our books.

• Past excerpts can be found by hitting “Excerpts” in the tags blow this post.

[pic]