It oozes, it undulates, it never stops…and it never goes away. Most people thought Lava Lamps had died and joined Nehru jackets in pop culture heaven. But no—they’re still around. Here’s a quick course on the history and science of lava lamps.

Egg-straordinary History

Shortly after leaving the Royal Air Force at the end Light Duty Craven-Walker saw a timer into a lamp and sell it to the public. He tracked down its inventor, a man known today only by his last name, Dunnet, only to find he had died—without patenting his invention. So Craven-Walker was able to patent it himself.

Craven-Walker spent the next 15 years perfecting the lamp so it could be mass-produced. In the meantime, he supported himself by making “art-house” films about his other passion: nudity. (In those days, pornography was illegal in many places, and the only way around the law was by making “documentaries” about nudism. Whether he was a genuine nudist or just a pornographer in disguise is open to interpretation.)

Coming to America

In 1964 Craven-Walker finished work on his lamp—a cylindrical vase he called the Astrolight—and introduced it at a novelty convention in Hamburg, West Germany, in 1965.

Two Americans, Adolph Wertheimer and Hy Spector, saw it and bought the American rights. They renamed it the Lava Lite and introduced it in the U.S., just in time for the psychedelic ’60s.

“Lava Lite sales peaked in the late sixties,” Jane and Michael Stern write in The Encyclopedia of Bad Taste, “when the slow-swirling colored wax happened to coincide perfectly with the undulating aesthetics of psychedelia….They were advertised as head trips that offered ‘a motion for every emotion.’ ”

Floating Up…and Down…and Up…

At their peak, more than seven million Lava Lites (the English version was called a Lava Lamp) were sold around the world each year, but by the of World War II, an Englishman named Edward Craven- Walker walked into a pub in Hampshire, England, and noticed an odd item sitting on the counter behind the bar. It was a glass cocktail shaker that contained some kind of mucous-like blob floating in liquid. The bartender told him it was an egg-timer.

Actually, the “blob” was a clump of solid wax in a clear liquid. You put the cocktail shaker in the boiling water with your egg, the bartender explained, and as the boiling water cooked the egg, it also melted the wax, turning it into an amorphous blob of goo. When the wax floated to the top of the jar, your egg was done.

In early 1970s, the fad had run its course and sales fell dramatically. By 1976 sales were down to 200 lamps a week, a fraction of what they had been a few years before. By the late 1980s, however, sales began to rebound. “As style makers began to ransack the sixties for inspiration, Lava Lites came back,” Jane and Michael Stern write. “Formerly dollar-apiece fleamarket pickings, original Lava Lites—particularly those with paisley, pop art, or homemade trippy motifs on their bases—became real collectibles in the late eighties, selling in chic boutiques for more than a brand new one.” Not that brand-new ones were hurting for business—by 1998 manufacturers in England and the U.S. were selling more than 2 million a year.

Lava Light Science

Grooovy, Baby!

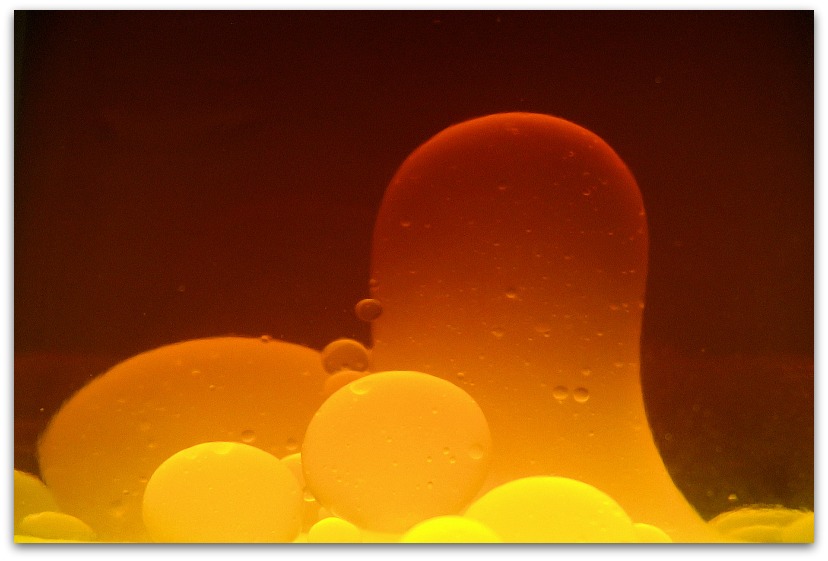

- When the lamp is turned off and at room temperature, the waxy “lava” substance is slightly heavier than the liquid it’s in. That’s why the wax is slumped in a heap at the bottom.

- When you switch on the bulb and it begins to heat the fluid, the wax melts and expands to the point where it is slightly lighter than the fluid. That’s what causes the “lava” to rise.

- As the wax rises, it moves farther away from the bulb, and cools just enough to make it heavier than the fluid again. This causes the lava to fall back toward the bulb, where it starts to heat up again, and the process repeats itself.

- The lava also contains chemicals called “surfactants” that make it easier for the wax to break into blobs and squish back together.”

- It is this precise chemical balancing act that makes manufacturing the lamps such a challenge. “Every batch has to be individually matched and tested,” says company chemist John Mundy. “Then we have to balance it so the wax won’t stick. Otherwise, it just runs up the side or disperses into tiny bubbles.”

For more weird facts from the weird world around you, check out Uncle John’s Weird, Weird World.