When economists want to get a sense of how the economy is doing, they look at things like the prime lending rate, the unemployment rate, and the Dow Jones Average. It turns out that’s not all they look at. (This article was originally published in Uncle John’s Weird Weird World EPIC.)

Down Under

What interested Greenspan about men’s underwear was that the sales figures rarely changed. For most men, underwear isn’t something they treat themselves to when they feel like splurging; it’s a purely utilitarian item. They buy it to replace underwear that has worn out. And since underwear wears out at a pretty steady rate, sales of new underwear are pretty steady too.

Greenspan noticed, however, that on occasion underwear sales did dip. When that happened, he interpreted it to mean that significant numbers of men were financially stressed enough that they had stopped replacing their worn-out shorts.

First Things First

How many people see you in your underwear? When funds are limited, most men will put off buying underwear—clothes that people don’t see—before they stop buying shirts and pants that people do see, if for no other reason than to keep up appearances.

If they have kids, men will put off buying their own underwear before they’ll stop buying things for their children. For this reason, men’s underwear sales tend to lead many other economic indicators— they register signs of economic distress months before sales of other items begin to slow. That’s why Greenspan liked to keep an eye on it: If the economy was losing steam, he’d see it in men’s underwear first.

This, That, and the Other Things

Over the years, economists have developed theories based on a lot of other items besides men’s underwear. For example:

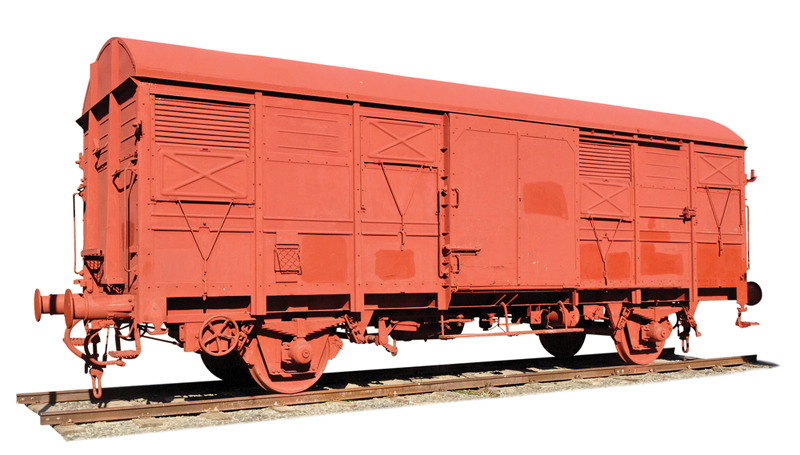

Boxcars. A lot of freight is shipped by rail in the United States, and when the freight isn’t moving, the unused boxcars are parked on railroad spur lines until the economy picks up and they’re needed again.

Movie Tickets. As expensive as a trip to the multiplex is nowadays, it’s still a lot cheaper than a weekend at the beach. People who can’t afford to take a vacation often compensate by going to the movies instead, causing ticket sales to rise in a recession.

Donuts. People who can’t afford a full breakfast in a restaurant will often trade down to a donut and coffee. Hot dog sales do well in hard times for the same reason: In the 1930s, they were known as “Depression sandwiches.”

Laxatives. When people are under stress and living on donuts and hot dogs…well, you figure it out.

Lipstick. Studies show that women who don’t have the money for a new dress or new shoes will spend $15 or $20 on lipstick instead. Belts, scarves, bracelets, and other fashion accessories that dress up old outfits also do well, as do home permanents and dye kits that offer a cheap alternative to hair salons.

Alligators. Most gators that end up as boots, handbags, and other designer goods are raised on farms. Sales of these items tend to crash during a recession (they’re too expensive and too flashy in hard times), and the alligator population on these farms explodes.

Lightbulbs. When Jack Welch took the helm at General Electric in 1981, the company made more than just lightbulbs, but he still swore by sales of bulbs as an indicator of where the economy was heading. “When people are affluent, they go to the store and buy what’s called ‘pantry inventory,’” he told an interviewer in 2001. “They’ll buy a pack of six or a pack of eight, and they’ll wait for the lights to go out. When times are tough, a light burns out, they’ll go buy one to replace the one went out. There are probably a thousand better indicators, but that one’s never been wrong.”