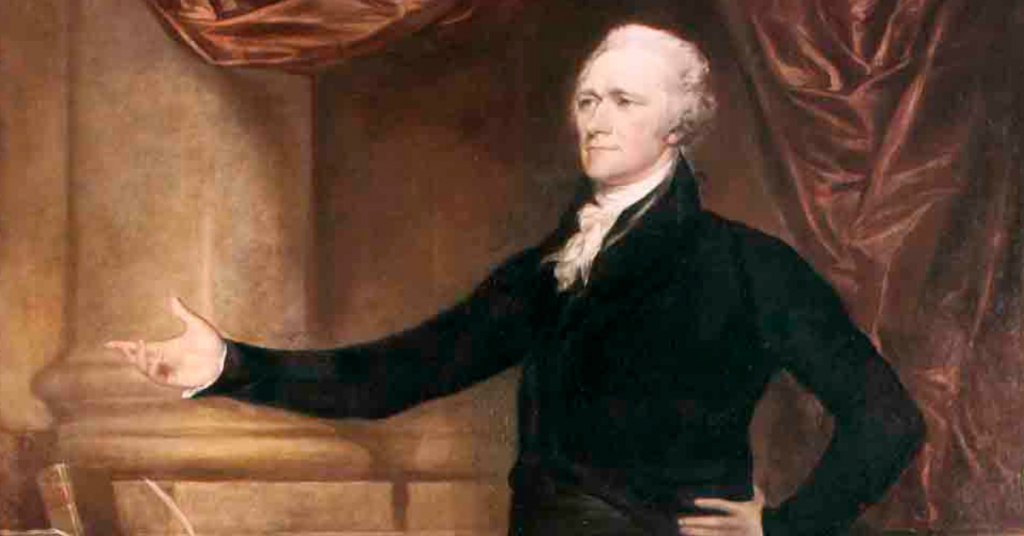

After the birth of North America’s first political party: the Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, the road was paved to create the two parties that we are most familiar with today: The Republican and Democratic parties. Here is how those to parties came to be. This article was first published in Uncle John’s Political Briefs. (Click here for the first part of the story.)

Meeting of the Minds

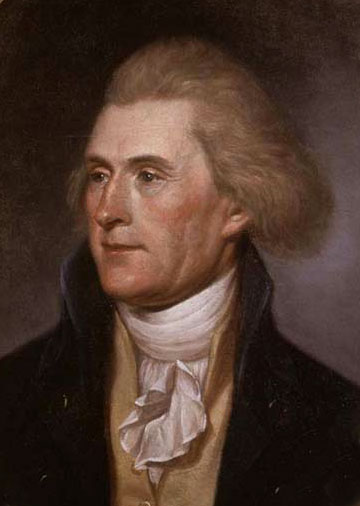

Jefferson, Madison, and the others saw themselves as defenders of the new republic against Hamilton and the “monarchical Federalists.” The party they formed became known as the Democratic-Republicans, or Republicans for short. Historians consider them the first opposition party in U.S. history, as well as the direct antecedent of the modern Democratic Party.

The Alien and Sedition Acts

The Democratic-Republicans lost their battle: Hamilton pushed his bank legislation through Congress, and President Washington signed it into law. They lost another major battle in 1792 when Governor Clinton ran against John Adams for vice president and lost. A third defeat came in 1796 when Washington declined to run for a third term as president: Jefferson ran for president against Vice President Adams…and lost by only three electoral votes.

In 1793 France—which was in the throes of its own revolution—declared war against England, giving the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans something new to disagree about. The Jeffersonian Republicans sided with republican France, and the Federalists sided with England. But neither side thought the United States should get involved in the war. Partisan emotions intensified in 1796, when the French began an undeclared war on American shipping as part of their war against England and refused to receive President Adams’s minister to France.

Angered by the insults, the Federalists began preparing for what they thought was an imminent war with France. They tripled the size of the army, authorized the creation of the U.S. Navy (the Continental Navy had been disbanded in 1784), and then in the face of the unanimous opposition of the Democratic-Republicans in Congress, passed what became known as the Alien and Sedition Acts.

The Alien Acts said that aliens (who were assumed to have Democratic-Republican leanings) had to live in the United States for 14 years—up from 5—before they would be eligible to vote. The acts also permitted the detention of citizens of enemy nations and increased the president’s power to deport “dangerous” aliens. The Sedition Act outlawed all associations whose purpose was “to oppose any measure of the government of the United States,” and imposed stiff punishments for writing, printing, or saying anything against the U.S. government.

Reading Between the Lines

By the time the Alien and Sedition Acts expired or were repealed four years later, only one alien had been deported and only 10 people were convicted of sedition, including a New Jersey man who was fined $100 for publicly “wishing that a wad from the presidential saluting cannon might ‘hit Adams in the ass.’”

But no one knew that back in 1798. To Jefferson and his supporters, it was obvious that the Alien Acts, and especially the Sedition Act, were targeted at them. Republicans could now be fined or jailed for speaking out against the Adams administration, and if they weren’t U.S. citizens, they could even be deported.

The fact that the Sedition Act expired after the 1800 presidential election seemed to prove their suspicions that the law was intended to curb Anti-Federalist dissent. While the acts were in force, Adams and the Federalists were legally protected from Democratic-Republican criticism, but if they happened to lose the 1800 election, the expiration of the Sedition Act would leave them free to criticize the Democratic-Republicans.

There was more: The Democratic-Republicans also feared that Adams, having tripled the size of the army, would begin using it against his political opponents. As if to confirm their fears, in 1799 Adams called out federal troops to put down an anti-tax rebellion led by Pennsylvania farmers opposed to taxes levied for the anticipated war with France.

The Democratic-Republicans were convinced that if the Federalists remained in power, democracy’s days were numbered, so they embarked on their strongest effort yet to capture the White House and Congress.

A Tough Call

John Adams had mixed feelings about running for reelection. He hated living in Washington, D.C., and he hated being president. The president “has a very hard, laborious, and unhappy life,” he warned his son John Quincy Adams. “No man who ever held the office of president would congratulate a friend on obtaining it.” And now that he was completely toothless, he was incapable of making public speeches in support of his candidacy for reelection.

The only reason Adams ran at all was because he was determined to prevent Jefferson from getting the job. Adams liked Jefferson personally, but he saw himself and Jefferson as “the North and South poles of the American Revolution.” He strongly disagreed with Jefferson’s views on government and the Constitution, and feared that Jefferson would drag the country into a European war to defend France.

Change of Fortune

The Democratic-Republicans, who believed that freedom was on the line, had no such reluctance—although Jefferson, announcing that he would “stand” for election rather than “run” for it, remained at his Monticello estate during the campaign. The party fought a hard campaign for him.

Federalist Farewell

The Federalists had accomplished much in the years following the Revolution: They had succeeded in drafting the U.S. Constitution, which strengthened the power of the federal government; they had enacted economic programs that strengthened credit and helped the economy grow.

But by 1800 their best days were behind them. “Federalism, as a political movement, was a declining force around the turn of the century,” historian Paul Johnson writes in A History of the American People, “precisely because it was a party of the elite, without popular roots, at a time when democracy was spreading fast among the states. Adams was the last of the Federalist presidents, and he could not get himself reelected.”

The Last Straw

It got worse for the Federalists. They vehemently opposed the War of 1812, and in the fall of 1814, when things seemed to be going very badly for the United States, Federalist delegates from New England met secretly in Hartford, Connecticut, to draft a series of resolutions listing their grievances with the federal government, which a negotiating committee would then bring to Washington, D.C. Some of the delegates to the secret convention had even discussed seceding from the Union.

Bad timing: By the time the negotiating committee arrived in Washington to protest the war, it was not only over, it had actually ended on a positive note, thanks to General Andrew Jackson’s victory in the Battle of New Orleans.

When the rest of the country learned that the Federalists had been holding secret meetings to contemplate splitting off from the rest of the country, the party’s image took a pounding. “Republican orators and publicists branded the Hartford convention an act of subversion during wartime,” A. James Reichley writes, “ending what was left of Federalism as a political force.”

But the die was cast. In spite of themselves, the Founding Fathers had created what they most feared: political factions. The era of the two-party system in the United States had begun.