Part man, part machine—and all real stories of people with robot parts.

Finger

Finnish computer programmer Jerry Jalava lost his ring finger in a motorcycle accident. He replaced it with a prosthetic finger of his own design—it’s also a computer flash drive. It looks like a normal finger (a shiny plastic one), but Jalava can pull back the nail, plug it into the USB slot on his computer, and store data files. (Ironically, these drives are sometimes called “thumb drives.”)

Knee

Brad Halling served in the Army’s Special Forces during the 1993 U.S. intervention in Somalia. A grenade hit his helicopter, and Halling lost his leg in the attack. In 2007 he received the most sophisticated joint replacement ever built: the Power Knee. Connected to two prosthetic leg parts, a microprocessor in the $100,000 device receives a signal from a small transmitter strapped to Halling’s other leg. The microprocessor senses how he’s moving and directs the robotic knee’s electric motor to copy the muscle movements. In short, he can walk normally. The downsides: It makes a loud whirring noise and has to be charged every night.

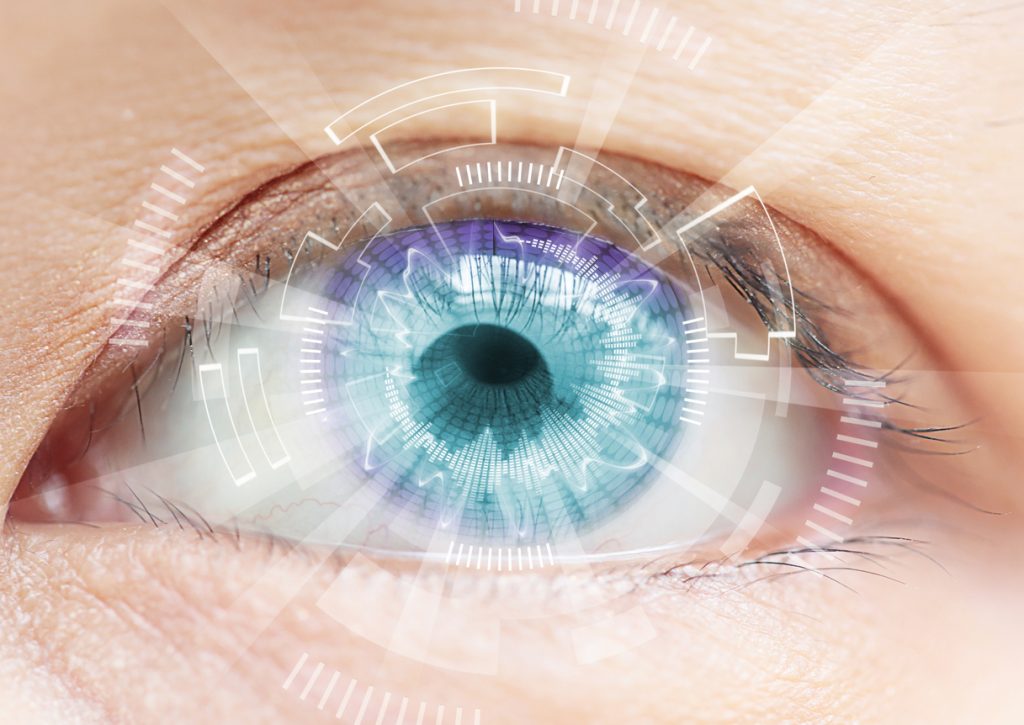

Eye

Canadian filmmaker Rob Spence lost the use of his right eye in a childhood gun accident. So, inspired by the tiny camera on his cell phone, in 2009, Spence decided to make the ultimate firstperson-POV film…by installing a prosthetic eye that is also a camera. A team from the University of Toronto is building the eye-camera (or “Eyeborg,” as Spence calls it), which will record video and send it wirelessly to a computer.

Bones

Researchers in the U.S. military may have found a way to regenerate human limbs. They use a technique called nanoscaffolding, in which tiny, cell-sized nets made of fiber optics hundreds of times thinner than a human hair are attached to the end of a missing limb. This structure acts as a framework where cells can congregate and bond into bones and tissue, growing through tiny holes in the scaffolding. The procedure isn’t quite ready to try out on humans yet, but scientists believe that one day it may also be used to generate new organs.