You’ve heard the expression “as slow as molasses moving uphill in winter”? Here’s the story of something even slower. (This story is a sneak peek from our 30th annual edition, Uncle John’s Old Faithful Bathroom Reader, available November 2017.)

Crude Effort

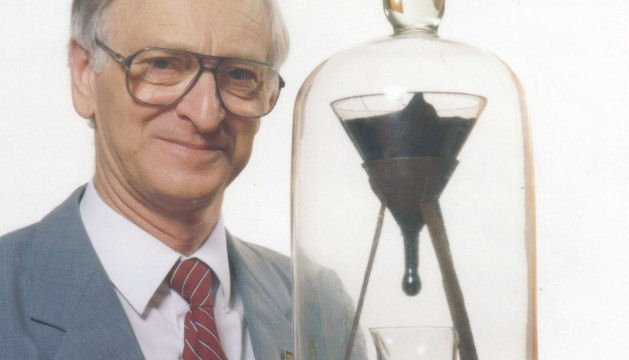

In January 1961 a man named John Mainstone began a new job as a physics lecturer at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia. On his first day, one of his colleagues showed him around the department, and in one room he pulled an experiment out of a cupboard. Still underway, it had been set up in the 1920s by Thomas Parnell, a physics professor long retired and now dead.

The experiment looked simple enough: it was a glass funnel filled with ordinary asphalt or “pitch,” a derivative of crude oil used to pave roads. The funnel sat on a stand, and beneath the stand was a glass beaker to catch any pitch that dripped from the funnel. A glass cover, called a bell jar, protected the apparatus from dust.

The “pitch drop experiment,” as it was called, had been sitting in the cupboard since the 1930s. In all that time, only three drops of the stuff had dripped from the funnel—the first in 1938, the second in 1947, and the third in 1954. A fourth was now hanging like a teardrop from the bottom of the funnel. It must have looked to Mainstone as if it could fall into the beaker at any moment, but as his colleague explained, years might pass before it finally did.

Drip…

Professor Parnell had created the experiment back in 1927 by pouring heated, softened pitch into a sealed funnel and letting it settle there for three years. In 1930 he unsealed the bottom of the funnel and the pitch began to flow. The purpose of the experiment was to demonstrate to his students that some substances, like pitch, may appear solid at room temperature but are actually very slow-moving liquids. If you hit a slab of pitch with a hammer, for example, it will smash into pieces, just like a rock. But if you put it in a funnel as Parnell did, it will slowly flow out, like water dripping from a faucet, because it’s actually a liquid, albeit one with extremely high viscosity, or resistance to flow. The pitch that Parnell placed in the funnel was so viscous that it took, on average, eight years for a single drop to form and drip from the funnel.

Pitching in…

Mainstone was fascinated by the experiment and agreed to become its custodian. His job: check the display once or twice a day to see how the fourth drop was progressing. He suggested that the experiment be taken out of the cupboard and placed on public display, so that other people could enjoy it as well.

The head of the physics department rejected the idea, insisting that “nobody would be the slightest bit interested.” There were even people who wanted to toss the display in the trash, but Mainstone managed to save it. It was still there in the cupboard in May 1962, when the fourth drop fell into the beaker…and no one was there to see it. It was still there eight years later in August 1970, when the fifth drop fell. Once again, nobody saw it. (In fact, no one had ever seen a drop of the pitch fall, because experiments like this one were rare, and it only takes about a tenth of a second for a drop of pitch to fall into a beaker. Managing to be there at just the right tenth of a second in that eight-year span takes persistence, dedication, and more than a little luck.)

The end is near…

A new head of the physics department took over in 1972, and he liked Mainstone’s suggestion of putting the pitch drop experiment on public display. So it was moved to the entrance hall of the physics building and set up in its own glass case. That’s where it was in April of 1979, when the sixth drop seemed close to falling.

Mainstone was determined to be there when it did fall. He wanted to understand the precise mechanical process that causes a drop to break free and fall into the beaker. He knew that in the final stages the drop hangs by three or four slender strands of pitch, and he theorized that the drop finally falls when one of those slender strands breaks, and the remaining strands are too weak to hold the drop any longer. But he couldn’t be sure until someone actually saw one fall.

One Saturday afternoon, the end appeared to be just days away. Mainstone had to decide whether to spend the rest of that day at work, in the off chance that it might drop, or go home, as he promised his wife, to help her around the house. After studying the drop carefully, he saw no signs of an imminent fall, and went home. He did not return Sunday, and by the time he arrived for work on Monday morning, the drop had fallen, again with no one to witness it.

Mainstone’s next chance came in the summer of 1988, when the seventh drop was getting near. This time he kept a close watch on the experiment. But as he recounted to an interviewer in 2013, at some point “I decided that I needed a cup of tea or something like that, walked away, came back, and lo and behold it had dropped. One becomes a bit philosophical about this, and I just said, ‘Oh well, let’s be patient.’ ”

Pitch Imperfect…

The wait for the eighth drop to fall took even longer, because the university installed air conditioning in the physics building, and cooler temperatures made the pitch flow more slowly. This time Mainstone had to wait 12 years, until November 2000, for the drop to fall. By then he was semi-retired and traveling in the UK when he received an e-mail from a colleague warning that the fall might happen at any moment. Mainstone was disappointed that he wouldn’t be there to see it in person, but he took comfort in knowing that the physics department had set up a camera to record the event…that is, until two more e-mails arrived. The first reported that the drop had fallen; the second reported that the camera had malfunctioned and failed to film the fall. Four times since 1962, drops had fallen into the beaker. Mainstone missed them all.

To the last drop…

By the summer of 2013, Mainstone was in his late 70s. He was still the custodian of the pitch drop experiment, and he hoped to be there to see the ninth drop fall, perhaps in 2014. This time, not one but three cameras were set up to film the drop, so that one camera would film the action even if two others failed. But Mainstone didn’t make it. He died in August 2013, before the drop fell.

Mainstone did have one consolation before he died: Trinity College in Dublin had their own pitch drop experiment, dating to 1944. It had been long ignored, but the growing interest in Mainstone’s experiment convinced the faculty at Trinity to pull theirs off the shelf, where it sat beneath decades of accumulated dust. A number of drops had already fallen, but no one knew when, because no one had paid any attention. This time would be different: When someone noticed in April 2013 that a drop looked like it was about to fall, a camera was set up to record it. At about 5:00 p.m. on July 11, it filmed the pitch as it fell into the beaker. Mainstone saw the footage; it was “tantalizing,” he told his colleagues. He died six weeks later.

Even if Mainstone had lived, he wouldn’t have seen the ninth drop fall. The beaker was so full of pitch from the first eight drops, that in April 2014 Mainstone’s successor decided to replace it with an empty one. But when he lifted the bell jar, the base wobbled and the ninth drop just snapped off. Don’t despair, though: the tenth drop should fall sometime in 2028, and there’s enough pitch in the funnel to last another 100 years.