One of the greatest moments of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. But it wasn’t planned that way. (This article was first published in Uncle John’s Triumphant 20th Anniversary Bathroom Reader.)

The March That Wasn’t

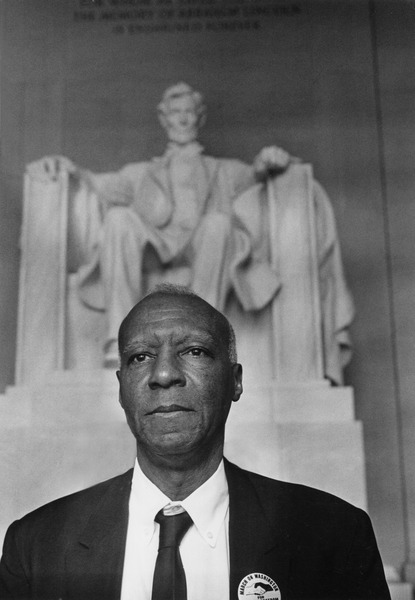

Philip Randolph

In 1941 A. Philip Randolph, founder and president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, one of the first African-American civil rights organizations, called for a march on Washington, D.C., in order to pressure President Franklin D. Roosevelt into providing wartime job opportunities for black men and women. When Roosevelt finally gave in and issued an executive order desegregating defense industries, the march was called off.

Twenty years later, Randolph felt the time had come again for a protest march in Washington. On July 2, 1962, he met with the nation’s most influential civil rights leaders, including Roy Wilkins, president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); James Farmer of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE); Whitney Young Jr. of the National Urban League; John Lewis of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC); veteran civil rights organizer Bayard Rustin; and Martin Luther King, Jr., chairman of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

The group decided a March on Washington would be held the following August. Rustin, chief coordinator, produced a flyer to announce it, demanding “meaningful civil rights legislation; a massive federal works program; full and fair employment; decent housing; the right to vote; and adequate integrated education.”

Against It

Opposition to the March on Washington was widespread. Not only did Southern senators and congressman have negative opinion—many others who were allies of the Civil Rights movement also objected to the event.

- President John Kennedy worried that a mass gathering could undermine legislative efforts to pass his recently introduced Civil Rights Bill. He told the organizers: “We want success in Congress, not just a big show at the Capitol.”

- Malcolm X, representing the Nation of Islam, referred to it as “the farce on Washington” and threatened members who attended with suspension from the Nation.

- Stokely Carmichael of SNCC called it a “sanitized, middle-class version of the real black movement.”

- The United States’ largest labor organization, the AFL-CIO, declined to participate in the March, claiming neutrality.

There were also concerns from the law enforcement community, and even from some of the organizers, that there would be violence, either from the participants or from anti-civil rights groups. All District of Columbia police leave was canceled. The National Guard and Army paratroopers were put on emergency alert. Nearby towns gave their police forces special riot-control training. The sale of liquor was banned for the day; even the Washington Senators baseball games were postponed. The federal Justice Department and the police worked with the march committee to develop a high-tech public address system, which the police then secretly rigged so they could take control of it if they saw fit. Perhaps the most cynical view of the meaning of the rally was over the site itself. A hundred years after the Emancipation Proclamation, the Lincoln Memorial represented all the collective hopes and dreams of the marchers. For the police, their dream was a site in which all those people could be contained on three sides by water.

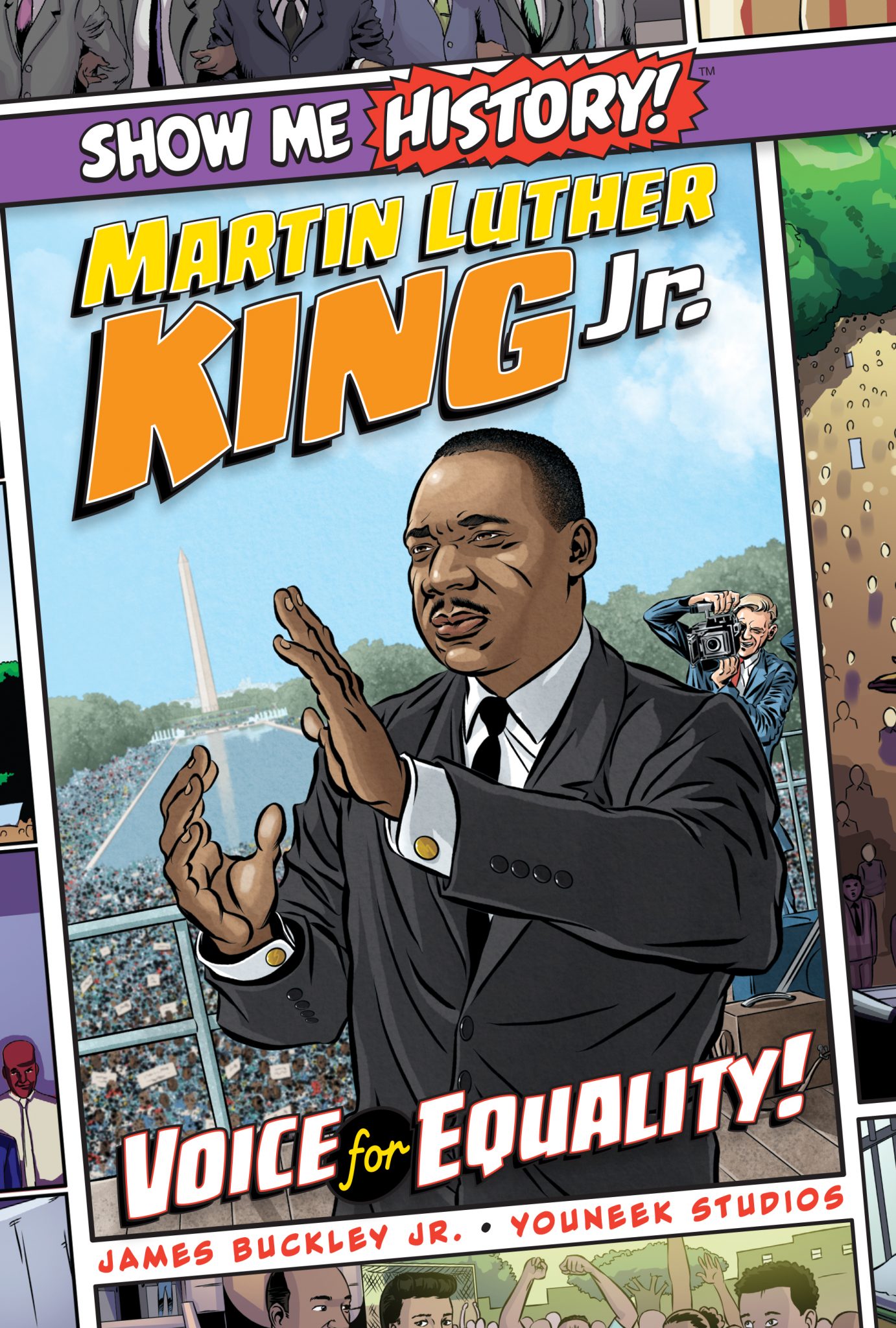

Martin Luther King Jr.: Voice for Equality! (Show Me History!)

News Coverage

The heavy police presence turned out to be unwarranted—the March was passionate but peaceful. An estimated quarter of a mil- lion people marched from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial, about 25% white, 75% black, and many of the black participants were from middle-class neighborhoods in Northern cities. It was the largest political demonstration in the United States to date. Media coverage was extensive, carried live on all three broadcast networks and internationally. There were more cameras than at the 1960 presidential inauguration. One television camera—positioned atop the Washington Monument— provided the dramatic shot of the March most people remember today: a sea of demonstrators a third of a mile long filling the narrow swath of land surrounding the reflecting pool.

The heavy police presence turned out to be unwarranted—the March was passionate but peaceful. An estimated quarter of a mil- lion people marched from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial, about 25% white, 75% black, and many of the black participants were from middle-class neighborhoods in Northern cities. It was the largest political demonstration in the United States to date. Media coverage was extensive, carried live on all three broadcast networks and internationally. There were more cameras than at the 1960 presidential inauguration. One television camera—positioned atop the Washington Monument— provided the dramatic shot of the March most people remember today: a sea of demonstrators a third of a mile long filling the narrow swath of land surrounding the reflecting pool.

The Speech

The all-day event included hundreds of speakers: civil rights leaders, labor leaders, politicians, celebrities such as James Baldwin, Charlton Heston, Sidney Poitier, Paul Newman, Harry Belafonte, and Marlon Brando, with singing performances from Josephine Baker, Eartha Kitt, Marian Anderson, Joan Baez, Sammy Davis Jr., folk trio Peter, Paul and Mary, and Bob Dylan. There had been a lot of wrangling among March organizers about who would speak and for how long. Dr. King agreed to be the last speaker. Rivals thought that tired marchers would be gone by then, and live TV coverage would have ended. But the network cameras and the crowd waited to hear him.

The all-day event included hundreds of speakers: civil rights leaders, labor leaders, politicians, celebrities such as James Baldwin, Charlton Heston, Sidney Poitier, Paul Newman, Harry Belafonte, and Marlon Brando, with singing performances from Josephine Baker, Eartha Kitt, Marian Anderson, Joan Baez, Sammy Davis Jr., folk trio Peter, Paul and Mary, and Bob Dylan. There had been a lot of wrangling among March organizers about who would speak and for how long. Dr. King agreed to be the last speaker. Rivals thought that tired marchers would be gone by then, and live TV coverage would have ended. But the network cameras and the crowd waited to hear him.

Most of King’s speech had been written the night before; much of its content and phrases he’d used many times. As he wrote in his autobiography, “The night of the 27th, I got into Washington about ten o’clock and went to the hotel. I thought through what I would say, and that took an hour or so. Then I put the outline together. I did not finish the complete text of my speech until 4:00 A.M. on the morning of August 28.”

Following a powerful performance from gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, King stepped up to the podium to read his speech, delivered in intentionally short phrases to meet the four-minute time limit. And then something happened: “I started out reading the speech, and read it down to a point. All of a sudden this thing came to me. The previous June, I had delivered a speech in Cobo Hall, in which I used the phrase ‘I have a dream.’ I had used it many times before, and I just felt that I wanted to use it here. I don’t know why. I hadn’t thought about it before the speech. I used the phrase, and at that point I just turned aside from the manuscript altogether.”

He may have used the phrase before, but the inspiration he received from that huge crowd, calling out to him, repeating his words back; the power of the moment, standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial, allowed him to improvise for over 10 minutes, turning four minutes of remarks into a 16-minute oratory that will never be forgotten.